SANCTUARY FROM THE STORM

Updated 2014-06-20 06:06:57

Hidden at the end of a pathway that breaks off from Mao Tse Tung Boulevard in Phnom Penh is a temple of a different kind, where seances are sacrosant and French writer Victor Hugo – author of Les Miserables – is considered a saint.

Worshippers there practise Caodaism, a southern Vietnamese religion that combines foundational elements of a handful of the world’s biggest faiths. Those who enter the temple find themselves welcomed by a fusion of religious imagery, including symbols from Buddhism and Christianity.

But in the face of heightened anti-Vietnamese sentiment in the past year, the Caodai temple, in Dangkor district, has become a sanctuary of a different kind to its congregation, which predominantly comprises ethnic Vietnamese.

“When I have trouble and feel unhappiness, I come here to attend a ceremony and recite Caodai songs and prayers. Then I have a fresh feeling and every worry or concern seems to be released from my body,” Seng Bun Hong, 56, said.

Anti-Vietnamese sentiment, which has a long and complicated history in the Kingdom, has been roused again after featuring prominently in the rhetoric of the opposition Cambodia National Rescue Party both in the lead-up to and following last July’s national election.

It has brought a heightened sense of unease into many lives and, at times, descended into violence.

In February, a 30-year-old Vietnamese-Cambodian was beaten to death by a mob in Phnom Penh’s Meanchey district after a confrontation erupted between a group of ethnic Vietnamese and bystanders at the scene of a traffic accident.

The incident came little more than a month after angry crowds at the height of a garment strike looted and trashed several shops owned by ethnic Vietnamese.

As tensions have become more overt, the temple has proven a safe zone for its people, even amid suggestions it is under the direct control of Vietnamese authorities. The last incident of targeted violence at the temple was minor and took place back in 1995. Even then, only a rock was thrown.

But according to academic Thien-Huong Ninh, a professor of religion at Williams College in the US, the temple has constantly been “on the edge of dissolution because of anti-Vietnamese Khmer nationalism in Cambodia”.

“The Caodai Vietnamese are much more vulnerable than other non-Caodai Vietnamese to anti-Vietnamese rhetoric in Cambodia,” she wrote in an email.

“Caodaists have been forced to practise their faith underground or drastically alter their religious rituals.”

Despite this, the temple itself has assumed a peaceful place in Cambodian society, partly due to it serving a peaceful “mediating role between the two countries”, Ninh documents in an article “God Needs a Passport”.

“The temple has become a meeting ground for Cambodian and Vietnamese politicians, who visit regularly, not only to express friendship and financial support, but also to share news and discuss political matters.

“In turn, the temple’s Management Committee is also responsible for informing the two governments on issues pertaining to religious life and to the position of Vietnamese in Cambodia,” she added.

The temple’s importance to its congregation has only increased since last July’s election, according to Ang Chanrith, director of the Minority Rights Organization [MIRO].

“Considering the violence that has occurred here in the past with anti-Vietnamese rhetoric, places in Cambodia where safety can be found have certainly grown in importance,” he said.

Combined forces

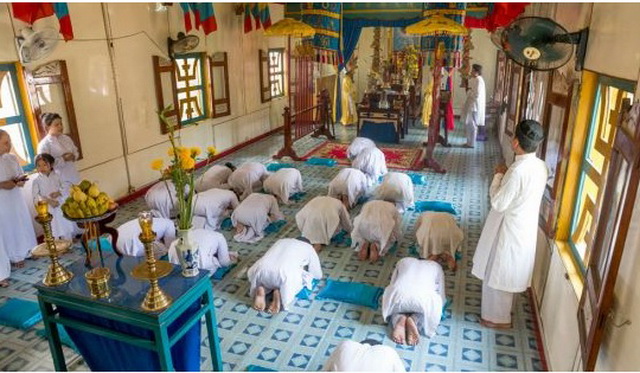

When the Post visited the temple, a group of men and women clad in white robes knelt before their representation of God – an image of an electric blue eye, hanging above an altar festooned with Technicolor banners.

Vietnamese chanting swallowed up the sounds of the city as a gong reverberated throughout the small garden where an empty crypt sleeps alongside a mash-up of religious iconography, starring Jesus Christ and Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat-Sen.

This collection of revered historical figures – among them the author Hugo – is believed to have been selected by spirits communicating to Caodai priests during seances.

Caodai, which means “high abode” or “roofless tower”, originated in the 1920s in the south of Vietnam, a country where more than a million people currently practise the religion.

According to Caodai lore, in 1920, the Venerable Cao Dai instructed Ngo Minh Chieu, a Vietnamese civil servant working for the French colonial administration, to create a doctrine fusing elements of Taoism, Confucianism, Christianity and Buddhism – in the name of world peace.

Some of the traditions associated with Caodaism are vegetarianism, gender equality and the belief that all deserve a proper burial regardless of religious background.

The epicentre of Caodaism, also known as the Caodai Holy See, is about 60 miles northwest of Ho Chi Minh City in Vietnam’s Tay Ninh province.

While Cambodia’s Caodaists number only about 2,000, the temple in Phnom Penh, which was founded in 1927, holds an impressive claim to fame. It was once the resting place of Pham Cong Tac, also known to followers as the “Defender of the Faith”, who sought asylum in Cambodia in 1959 after South Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh Diem took power.

According to temple authorities, his remains were repatriated to Tay Ninh in 2006.

Open to all

Although the religion’s roots are in Vietnam, its worshippers say that the temple is open to everyone.

“We welcome all because we want peace and happiness for all,” said 56-year-old Seng Bun Hong, adding that Caodaists believe that once an individual finds internal tranquillity, a more harmonious world becomes viable.

“It would be against our faith to discriminate against any individual, religion or even a political party,” adds Tran Minh, who has been living on the temple grounds along with 16 others for the past two years. Some, however, have suggested Vietnamese authorities control the temple, which, if true, could pose a threat to groups persecuted in Vietnam that take refuge there.

“According to our research, the Caodai temple is strictly controlled by the Vietnamese government through the Vietnamese Associations in Cambodia, despite it being located in Cambodia,” said MIRO’s Chanrith.

Temple director Vo Quang Minh said he “follows directions from the Holy See”, which is controlled by the Vietnamese government.

The Overseas Vietnamese Association declined requests for an interview, while Nguyen Yaing Min, the associate director of the Cambodia-Vietnam Federation in Kampong Chhnang, said that his association followed only “the rules and directions of the Cambodian authorities”.

Either way, the ethnic Vietnamese community at the temple say they have nurtured a place of peace, tucked away from any of the troubles their people may face.

“We live here peacefully, and we welcome all. We just want peace for the Khmer and Vietnamese. That is what Caodaists hold the most close,” Minh said.

A member of the Caodai temple opens a rotunda where an image of Jesus hangs. Scott Howes

A framed image of the Divine Eye hangs on a wall at a Caodai temple in Phnom Penh as devotees of

A gathering of worshippers pray at a Caodai temple in Phnom Penh last month. Scott Howes

Cao Dai Temple Director, Priest Vo quang Minh, prays at the altar

.jpg)