Dr. MOHAMMAD JAHANGIR ALAM TALKING ABOUT CAODAISM AT THE BSSCR VIRTUAL CONFERENCE

Updated 2021-06-01 00:57:57

(University of Dhaka, Bangladesh – May 30, 2021)

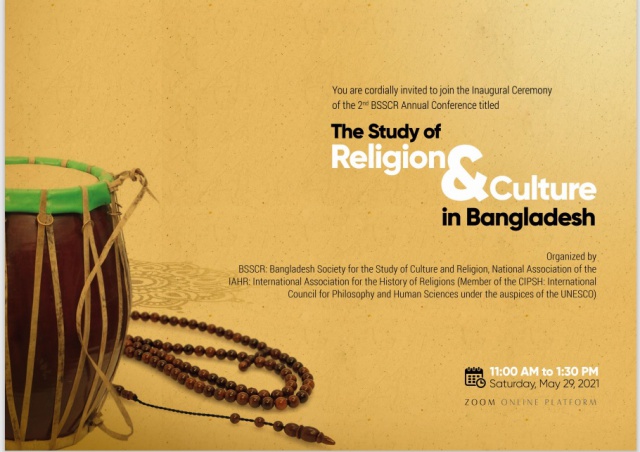

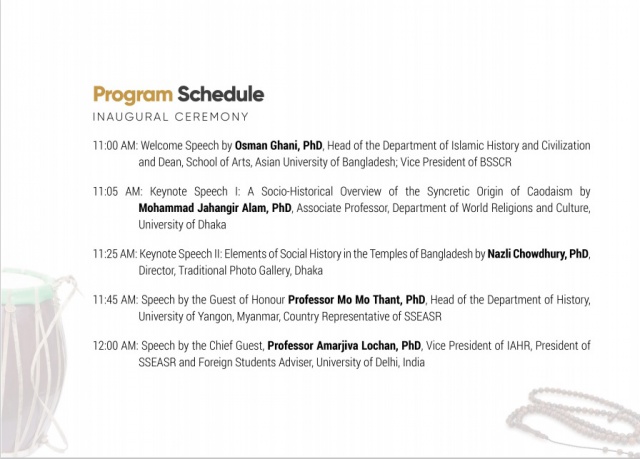

At the invitation of the Bangladesh Society for the Study of Culture and Religion (BSSCR), Dr. Mohammad Jahangir Alam delivered a Keynote Speech on A Socio-historical Overview of the Syncretic Origin of Caodaism at the 2nd Annual Conference of the BSSCR (online via google meet) on Saturday, May 29, 2021 at 11 am.

Dr. Alam is an Associate Professor of the Department of World Religions and Culture at the University of Dhaka, Bangladesh. He is considered as an expert on Caodaism. He had his Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts on Sep 2020 for the thesis entitled : ”Dao Cao Dai : A Social Historical Analysis of a Syncretic Vietnamese Religion and Its Relationship to Other Religions.” He taught the course on Caodaism since 2009. His class always attracted about 70-80 students per academic year. For the past ten years, he went to many International Conferences on Religions making presentation on Caodaism).

The theme of the BSSCR Conference: Study of Religion and Culture in Bangladesh.

The BSSCR was established in 2018 to promote academic study of religions in Bangladesh throughout the nation in various universities, colleges and research institutes. BSSCR has become the National Association of the IAHR (International Association for the History of Religions). IAHR is a member of the CIPSH (International Council for Philosophy and Human Sciences) under the auspices of the UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization).

Religion and culture have a fine and finite relationship, academic study of these two factors are very pertinent for continuous sustainable growth and development of a particular society.

Professor Najma Khan Majlis is the President of BSSCR.

Various scholars of religion and culture, members of BSSCR, SSEASR (South and Southeast Asian Association for the Study of Culture and Religion) and IAHR have attended the conference.

To view the presentation of the keynote speaker, Dr. Mohammad Janhangir Alam, please click this link

A Socio-historical Overview of the Syncretic Origin of Caodaism

Dr. Mohammad Jahangir Alam

Department of World Religions and Culture

University of Dhaka – Bangladesh

ABSTRACT

In the current paper Cao Dai religion is presented as one of the best examples of the outcome of Western and Asian acculturation that occurred in the South of Vietnam down through the centuries. Thus, the current study makes it plain that Caodaism tends to be viewed as an outstanding example of a harmonious synthesis of both cultural as well as religious blends. First to be considered is the fact that this paper focuses Vietnamese socio-historical context with a view to gaining a more comprehensive understanding of its significant role the way it played in the process of fostering the emergence of Caodaism in the South of Vietnam beginning in the early 20th century.

INTRODUCTION

The origin of Cao Dai religion lies in its historical necessity when Vietnam was passing through a critical period in which the mass people suffered greatly from injustice. The totality of surrounding conditions and circumstances of the South of Vietnam both directly and indirectly affects the growth of Cao Dai religion. With regard to this common phenomenon, it may be relevant to present Daljeet Singh’s critical view: “No doubt, the environmental situation and the social milieu in which a religion arises do have their impact on its growth and the problems it seeks to tackle. Yet, it is very true that the perceptions, the internal strength, and the ideology of a religion are fundamentally the elements that give it substance and direction, and shape its personality” (Singh, 1984, p.1). The emergence of Cao Dai religion occurred at a time when several developments had come to a head. Fighting for its existence, it had been able to build up its position so that it could not easily be eradicated by its opponents.

According to Janet Hoskins, religious innovation always struggles against an established order that attempts to absorb or suppress it, but in a colonial context this struggle took on additional implications. For Werner, “despite its idiosyncrasies, the Cao Dai was in fact an important political and social movement generated by the colonial context of 1920s Vietnam” (Chapman, 2006, p.36).

SYNCRETIC ORIGIN OF CAODAISM: SOCIO-HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

During the early period of the Christian era particularly, the effects of Chinese culture were perceived abroad in Vietnam, Korea, and Japan. As one of the foremost world civilizations, China was creating a new synthesis of cultures in Chinese Buddhism (Smart, 1989). Historically, Chinese Buddhism arrived in Vietnam during the second half of the 1st Christian era while Taoism and Confucianism came to Vietnam long before the advent of Buddhism. As Taoism and Confucianism were not missionary religions, they did not proselytize to convert followers the way Buddhism could very radically reorient the Vietnamese societies. At the same time a new amalgamation of cultures in Vietnamese Buddhism started to be visualized. In the 19th century substantial migrations occurred under the influence of a growing colonialist world economy, and in consequence European culture and religion (French in particular) is to be found in Vietnam, Cambodia and Lao.

A systematic inquiry into the features of a religion and the structure of its society in a distinct area is needed to study and interpret its origin and development from the historical perspective. By this method individual features of a particular religion and its surroundings can be identified. At the same time, it is possible to become familiar with the structural elements of the society. As clear evidence of interrelationship and interaction between religion and society is marked there is a scope to consider how the possible social issues influenced the growth and development of Cao Dai religion in the early 20th century. The function of sociology of religion refers to the interrelationship and interaction of religion and society as its subject matter. The analysis of the definition of sociology of religion suggests that religion and society are independent, separate elements which may interact with each other. In his book Readings in the Sociology of Religion Joan Brothers analyze Joachim Wach’s view regarding the matter that for Wach religion is an integrating factor in human society, expressing itself in myth, dogma, cult and religious grouping (Brothers, 1967). It now may be asked how, from the complex structure of Southern Vietnamese society, the process of the origin of Cao Dai religion can be understood. As far as Vietnamese Spiritism is concerned, the relationship between religion and society is closely allied to the theological concept of natural and supernatural (1967b). Therefore, it may be assumed that like major religions of the world Cao Dai religion has developed its own distinctive orientation toward all aspects of social life. Sociologically speaking, a new faith creates a new world in which old conceptions and institutions may lose their meaning. The preaching of a new faith is addressed primarily to one group of people which may be more or less homogeneous. In culturally higher differentiated societies, the background of converts is often very heterogeneous (Wach, 1949). At this point Wach raises the question: How did the integration of a homogeneous group take place? Since we are concerned with the integration of Cao Dai religious group, the social conditions which favor or hinder it, and the means which were available for it, we might properly ask to what extent the different types of social factors contribute to the integration of Cao Dai community. In the case of Cao Dai religion, it is not difficult to find borrowed elements which will be characterized as identical because it shares the same cultic ties. After Cao Dai religion emerged on the basis of Vietnamese traditional folk beliefs, it absorbed a great deal of Tam Giao (three great teachings of Vietnam), the resultant blend, which may remain for centuries a powerful integrating factor in the Vietnamese life.

THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF CAODAISM

Many religious groups are seen to have their roots in popular expressions (McGuire, 1997). If the social construction of Cao Dai religion is taken into consideration from historical perspective, at least since the beginning of the 20th century, there still has been a strong connection between organized and popular forms of religion in Vietnam. This connection was taken for granted largely because, at the time of the origin and growth of Cao Dai religion especially since the mid-1920s, the official declaration of the new faith (1926) and its organization had successfully achieved politically legitimated cultural dominance throughout the South of Vietnam. Without questioning the social construction of Cao Dai religion can be identified as an official or organized form of religion like Judaism, Christianity, Islam and Bahai Faith. Thus, the notion of religious syncretism (the blending of diverse cultural elements into one religion) that was used to imply un-authentication or contamination has been proved to be wrong and invalid by recent anthropological study. In contrast to this idea, modern critics argue that syncretic process is considered the foundation of religion in contemporary anthropology. Thus, in the light of recent scholarship it may be assumed that the syncretic origin and nature of Caodaism will not expose its existence to any dangers in future.

FLEXIBILITY AND CONSOLIDATION OF CAODAISM

As a historical strength, like Roman Catholicism, due to Caodaism's flexibility in absorbing and, often, co-opting Vietnamese traditional cultural elements i.e., local popular cults as optional devotions, the Cao Dai church was able to build organizations that went beyond familistic, localistic, or cultic barriers. By placing the altar and transforming spirits into mediators for the whole congregation, the Pope (spiritual pope), for example, shifted the balance of social order in the Cao Dai community. Furthermore, the cult of Vietnamese Spiritism enabled Cao Dai religion to absorb and transform pre-Cao Dai pagan elements of indigenous cultures. This gradual consolidation of Cao Dai religion shows how it has become assimilated into the characteristic boundaries of Southern Vietnamese societies.

Notably, for a long time, Caodaism, with its strange mixture of Sino-Vietnamese tradition and to some extent Christian elements, remained the religion of a marginalized minority. Its Sino and Christian background is not just historical but essential. Therefore, Caodaism is constantly reminded of its links with religions of Chinese and Indian origin. For Thomas E. Dutton (1970), Caodaism combines important elements to harmonize the otherworldliness of the Indian tradition with the worldliness of the Chinese. With regard to its roots, as the historian R.B. Smith notes, Caodaism finds its roots in the “secret societies” (hoi kin) inspired by the local settlements of the Chinese Heaven and Earth Association (Thien dia). In addition, he also views it to be the direct product of Chinese or Sino-Vietnamese religious sectarianism, called Minh (Smith, 1970). However, for many scholars, despite its direct links with Taoism, Confucianism, Buddhism and Christianity, Caodaism developed independently within the pure Vietnamese milieu. In that particular case, what the Caodaists did was that they communicated using Vietnamese terminology and patterns of thinking. And notably, they could radically reorient many concepts and ideologies within the ideological sphere of Caodaism over a period of time. However, most certainly, the religion of any people develops over time; and so it has been for the Vietnamese Caodaists.

CONCLUSION

To understand Vietnamese religion today, it is important to have a historical knowledge of how Confucianism, Taoism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Christianity were introduced into Vietnam, how they interacted with the native tradition and how together with native spiritism, they fundamentally shaped the subsequent Vietnamese religious landscape that serves as windows to the Vietnamese people’s sense of identity. Cao Dai religion began as a minority sect in the matrix of Vietnamese Spiritism and three Great Teachings and in its spread to cultural settings; it gradually consolidated its position, achieving an effective monopoly of legitimacy under French administration in Cochinchina. Thus, it may be argued that the reason for Caodaism’s initial success was due to a confluence of religious traditions such as Taoist spiritism, Buddhist concepts of salvation and reincarnation. As Hoskins (2008) argues, what Caodaism added to the mix was a more personal form of monotheism or polytheism.

References

Singh, Daljeet. (1984). The Sikh Ideology. Guru Nanak Foundation.

Chapman, Jessica Miranda. (2006). Debating the Will of Heaven: South Vietnamese Politics and Nationalism in International Perspective, 1935-1956 [Doctoral thesis, Santa Barbara, University of California].

Smart, Ninian. (1989). The World’s Religions. Prentice Hall.

Joan Brothers, Joan. (1967). Readings in the Sociology of Religion (Eds.). Pergamon Press.

Wach, Joachim. (1949). Sociology of Religion. The University of Chicago Press.

McGuire, Meredith B. (1997) Religion: The Social Context (7th ed.). ITP.

Dutton, Thomas E. (1970). Caodaism as History, Philosophy, and Religion [Unpublished master’s thesis in Oriental Religions] University of California, Berkeley.

Smith, R. B. (1970) “An Introduction to Caodaism 1: Origins and Early History”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 33 (2):335-49.

Hoskins, J. (2008). From Kuan Yin to Joan of Arc: Female Divinities in the Caodai Pantheon. The Constant and Changes Faces of the Goddess in Asia, 80-99.